Mydriasis physiology

Mydriasis refers to physiologic or pharmacologic pupillary dilation. Physiologic pupillary dilation occurs naturally as a response to low light and viewing objects in the distance. This process is mediated by both the iris sphincter and the iris dilator muscles, the latter of which contracts in response to sympathetic stimulation and relaxes in response to parasympathetic stimulation. The pupillary dilation pathway is a three-neuron pathway that originates in the locus coeruleus and hypothalamus, and descends through the midbrain to synapse in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord. The preganglionic neuron exits the spinal cord near the apex of the lung and then travels superiorly to synapse in the superior cervical ganglion. Finally, the postganglionic neuron travels through the cavernous sinus and into the orbit to innervate the iris dilator muscle.1 Contraction of the iris dilator muscle pulls the inner iris outward, leading to mydriasis.2 Concurrently, the locus coeruleus sends inhibitory signals to the Edinger–Westphal nucleus to suppress pupillary constriction, mediated by the iris sphincter muscle.3

Clinical relevance and importance of pupillary dilation

Clinically, pupillary dilation is a standard part of a comprehensive eye examination. It is also important during intraocular surgery, such as cataract surgery, which is one of the most common surgeries performed worldwide.4 Intraoperatively, good pupillary dilation is crucial to provide an adequate surgical view and contributes to safer surgery and lower rates of complications.5 With regards to clinical examination, pupillary dilation remains the gold standard to examine the peripheral retina. In a study comparing the detection of diabetic eye disease with and without pupillary dilation, dilation doubled the sensitivity of fundoscopic detection of diabetic retinopathy.6 With an increasing prevalence of diabetes in the USA and worldwide, comprehensive examinations in this population are becoming increasingly relevant. Indeed, adherence to annual eye examination is associated with decreased rates of blindness in patients with diabetes.7–9 Common causes of visual impairment include age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma and cataracts, affecting an estimated 25% of elderly Americans.10 Given the burden of ocular diseases in this population, the National Eye Institute recommends that individuals 60 years and older receive a dilated eye examination every 1–2 years.11 Blindness is often a result of preventable and/or intervenable causes, illustrating the importance of comprehensive eye examinations for screening and early diagnosis.12–14 Additionally, in children, regular vision screening is recommended, and following screening recommendations can reduce vision loss from amblyopia by more than half.15

While most healthy asymptomatic children do not require routine dilated eye examinations, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends vision screening start around 3 years of age, and occur annually until at least the age of 6 years; and the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends children aged 3–5 years undergo vision screening at least once.16,17 The American Academy of Ophthalmology and American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus further recommend screening every 1–2 years after age 5. Despite this, there has been a downward trend in childhood vision screening.18–20 Children who fail vision screening are referred to ophthalmologists, who perform a dilated fundus examination and cycloplegic refraction. Cycloplegia is related to, but distinct from, mydriasis. While mydriasis refers solely to dilation of the pupil, cycloplegia refers to the process by which the muscles responsible for accommodation are paralyzed. Cycloplegia is necessary to obtain an accurate measurement of the eye’s refractive status in children given their more robust accommodation.21 During eye examinations, mydriasis is achieved through the use of mydriatic and cycloplegic agents.

Pharmacologic mydriasis and cycloplegia

Numerous pharmacologic agents are used to achieve mydriasis and pupillary dilation, with varying side effects, half-lives, and time to onset (Table 1).22 Atropine is an anti-muscarinic agent and the most potent cycloplegic agent available.23,24 Given its comparatively longer duration of action of 1–2 weeks, it is less commonly used. Its side-effect profile includes allergic reactions with conjunctivitis, eyelid oedema and allergic dermatitis, which may be more common with atropine compared with other cycloplegics.23,25 Due to its strong cycloplegic effects, atropine has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of certain types of amblyopia. By administering atropine in the non-amblyopic eye, the cycloplegic-induced blur can lead to improvements in the vision in the amblyopic eye.26 Additionally, newer studies suggest that doses of atropine as low as 0.01% may be useful in preventing progression of myopia for paediatric patients.27,28

Table 1: Commonly used mydriatic and cycloplegic agents22

|

Medication |

Available doses |

Onset |

Duration of effects |

|

Atropine sulfate |

1% |

45–120 minutes |

1–2 weeks |

|

Cyclopentolate hydrochloride |

0.2%*,0.5%, 1%, 2% |

30–60 minutes |

6–24 hours |

|

Phenylephrine |

1%*, 2.5%, 10%† |

15–30 minutes |

1–3 hours |

|

Tropicamide |

0.5%, 1% |

20–40 minutes |

4–6 hours |

*As a component of combination cyclopentolate-phenylephrine.

†Uncommonly used due to adverse effects.

Cyclopentolate, another muscarinic antagonist, is more frequently used in paediatric populations. Cyclopentolate is a more effective cycloplegic with a longer duration of action in comparison with other cycloplegics, which is particularly important for paediatric patients who may have difficulty cooperating with an examination.29,30 Available doses include 0.2% (when delivered via combination drop with phenylephrine), 1% and 2%. Cyclopentolate is used in conjunction with phenylephrine, with similar cycloplegic effects as tropicamide–cyclopentolate–phenylephrine solutions.31 The side-effect profile of this medication is quite similar to other antimuscarinic agents and may increase intraocular pressure (IOP), cause irritation and conjunctival hyperemia and, rarely, central nervous system effects such as restlessness, hyperactivity and ataxia.32,33

Phenylephrine is an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist, which acts by increasing sympathetic stimulation to the iris dilator, although it is not thought to have a major effect on accommodation.34 Available doses are 1% (when delivered via combination drop with cyclopentolate), 2.5%, and 10%. The higher concentration is typically avoided due to the risk of causing adverse systemic effects including tachycardia, bradycardia, hypertension in patients with pre-existing heart conditions, stroke and arrhythmia.23,35–38 Phenylephrine is often used in combination with tropicamide to achieve maximum mydriasis.

Tropicamide, a non-selective muscarinic antagonist, suppresses the parasympathetic drive, relaxing both the iris sphincter (mydriasis) and ciliary muscles (cycloplegia). The medication is generally safe, but reported side effects include increased IOP, irritation, dry mucus membranes, flushing and tachycardia.23,29 Rarely, tropicamide may cause central nervous system disturbances and psychotic reactions in paediatric patients.39,40 Tropicamide is available at doses of 0.5% and 1%. A common dilation regimen in adults is 1.0% tropicamide used in combination with 2.5% phenylephrine.34,41 Lastly, homatropine and scopolamine have also been used for mydriasis and cycloplegia, but these agents have longer administration schedules and are less commonly used.22,42

Combination therapy

Many ophthalmologists will administer some combination of the individual agents discussed above. This requires clinical staff to administer multiple drops of different medications. While effective at achieving mydriasis, this method may not be efficient and has led to consideration of combination eyedrop therapy. This approach has been effective in other domains. Fixed-combination therapy for glaucoma, for example, has been shown to provide greater convenience, adherence and tolerance, leading to greater reduction in IOP.43–45 Ideally, dilating agents should have a rapid onset and recovery, adequate mydriasis and limited side effects.46 Proparacaine is a topical anaesthetic agent that enhances absorption of other topical medications by disrupting the corneal epithelium, improving both onset and maximum mydriasis when used before tropicamide–phenylephrine combination drops or tropicamide alone.47,48 This method still is limited by requiring the administration of multiple medications. Theoretically, combining multiple mydriatic medications could potentially increase the risk of systemic side effects, but also could minimize this by allowing for a decrease in the dose of the individual agents. For example, a study comparing a fixed combination of tropicamide 0.5% and phenylephrine 0.5% to conventional individual tropicamide 1.0% and phenylephrine 2.5% found that both regimens were equally effective, but the lower dose fixed combination was better tolerated.46 Currently, fixed-combination eyedrops are not widely available in the USA and, where available, require production by specialty compounding pharmacies. Combination eyedrops have the potential to enhance patient comfort and increase clinic efficiency.

Novel drug delivery devices

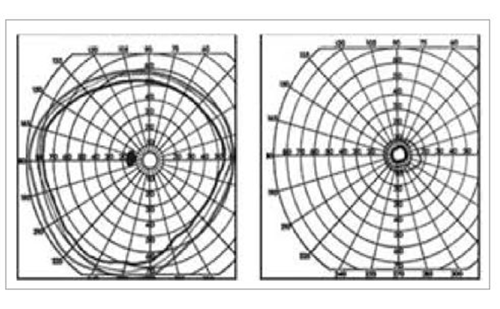

The size of standard eye drops ranges from 25 to 50 μL and exceeds the capacity of the tear film.49–51 The average tear film may retain up to 20 μL of fluid, thus drops over this volume have no therapeutic benefits and may be absorbed systemically, increasing the risk of adverse side effects.49,52–54 Thus, novel therapies have been devised which focus on providing a precise, direct and more efficacious method of medication administration with fewer side effects.55,56 Smaller-volume eyedrops have been employed as a way to address this concern. Brown and Hanna suggested in 1978 that smaller drop sizes were able to achieve similar levels of cycloplegia and mydriasis compared with regular drops.57 Subsequently, this group established that smaller drop size of clonidine substanstially lowers IOP in glaucomatous eye without additional systemic effects.58 Further research by several groups proved that, in infants, microdrops achieve similar levels of mydriasis without systemic effects and smaller plasma values.59–61 In comparison with larger drops, smaller-volume eyedrops have shown to be equally efficacious in mydriasis, cycloplegia and IOP reduction, with no difference or lower incidence of side effects.58,62–65 The Nanodropper (Nanodropper, Inc., Rochester, MN, USA) is a United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, commercially available device that attaches to most eyedrop bottles to administer small-volume drops of approximately 10.4 μL. Its design allows for increased precision with drop delivery, smaller drops and theoretically decreased systemic absorption.66 Research into this device is ongoing however; our group previously published a study in children which demonstrated that drops of 1% tropicamide, 1% cyclopentolate and 2.5% phenylephrine applied with the Nanodropper device achieved a similar level of mydriasis and cycloplegia compared to standard-of-care eyedrops, suggesting that this is a feasible approach.51 While strict noninferiority criteria were met only for pupillary dilation (p=0.02) and not for cycloplegia (p=0.22), the small differences between the groups were not clinically significant. Additionally, all eyes in both groups were able to achieve >6.0 mm pupillary dilation, which was considered clinically acceptable based on previously accepted clinical values.31

Another novel device uses Microdose Array Print (MAP) technology, which is also designed to deliver precise medication doses, with improvements in bioavailability and patient outcomes. MAP technology facilitated the development of fixed-combination 1% tropicamide 2.5% phenylephrine with the FDA-approved, commercially available Optejet® (MydcCombi™; Eyenovia, Inc., New York, NY, USA). This is a horizontal topical drug delivery system designed to rapidly deliver medication directly to the cornea.34 The smaller drop size and increased speed of delivery limit unnecessary exposure to medication and preservatives while reducing waste that may occur due to eyedrop overflow.34,67 MAP technology has been evaluated in phase II and phase III trials.34,67 A phase II study in 12 healthy adults without underlying ocular pathology aimed to compare efficacy and adverse effects of 2.5% and 10% phenylephrine eyedrops delivered conventionally, to 10% phenylephrine delivered using MAP technology. The primary outcome was pupil diameter measured by pupillometry at various times after drug delivery. At 75 min, maximum pupil diameter was comparable between 10% phenylephrine administered conventionally and via MAP technology (p=0.318). Maximum pupil diameter was superior, with 10% phenylephrine MAP compared with 2.5% phenylephrine conventional (p=0.009). Furthermore, MAP technology administration was associated with lower serum phenylephrine levels and better tolerated (adverse events in 1 subject versus 7 subjects in the MAP and conventional groups, respectively).

Two phase III trials, MIST-1 (Safety and efficacy of phenylephrine 2.5%-tropicamide 1% microdose ophthalmic solution for pupil dilation [MIST-1]; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03751631) and MIST-2 (Safety and efficacy of phenylephrine 2.5%-tropicamide 1% microdose ophthalmic solution for pupil dilation [MIST-2]; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03751098), aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a fixed combination 1% tropicamide 2.5% phenylephrine solution administered using the Optejet drug delivery system.34 A total of 131 subjects aged 12–66 years (mean 37 years) participated in the study. The MIST-1 trial was a crossover study comparing Optejet delivery of 3 different medication regimens: 1% tropicamide alone, 2.5% phenylephrine alone, or 1% tropicamide 2.5% phenylephrine fixed combination. Briefly, combination therapy achieved statistically significant greater change in pupil diameter compared with individual components of tropicamide or phenylephrine alone (4.72 mm, 4.11 mm, and 0.85 mm respectively, p<0.0001 for all treatment group differences from combination therapy). The MIST-2 trial compared fixed combination therapy to placebo. No adverse events were reported in the placebo group and 3% of participants reported adverse effects from the fixed combined solution (most severe being photophobia; other effects were mild, including blurry vision, instillation site pain and visual acuity reduction). Taken together, these trials provide solid evidence of this new technology to perform pupillary dilation with fewer adverse effects and equal efficacy.

Conclusion

Pharmacologic mydriasis and cycloplegia are a mainstay of comprehensive eye care. Several newer methods of drug delivery are aimed to improve effectiveness, drug administration, and reduce drug waste and adverse effects. Devices for drug delivery and novel medications are still in active development and preliminary studies demonstrate similar or improved efficacy to conventional forms of therapy. The ideal novel delivery mechanism will provide better tolerated and less wasteful medications to improve pharmacologic pupillary dilation for both patients and providers. Additional prospective studies will determine the role of these technologies in ophthalmic practice.